Measuring speed of the code: the wrong way

Sometime ago, I decided to measure the performance of my optimized code. It was a pure function, so I reckoned I could just wrap the whole thing in performance.now() and see how my changes affected the execution time. I was thrilled to see that I had shaved off about 800ms from the total time of 2s 🎉. I unplugged my laptop from the monitor cable (which also acted as a charger) and brought my computer to a friend’s desk to, eager to show my achievement. It was a quite embarrassing when, during my proud demonstration, my ‘optimization’ seemed to take about 400ms longer than the original code did…

Part 1: Don’t trust V8

V8, Google’s JavaScript engine, may “decide” to optimize, deoptimize, and cache your code, and these “decisions” will affect the execution time.

Say we have a function doSomething(). Before optimizing it, we want to see the initial performance, so we wrap it in performance.now() and start our Node server. We see that the function took 1 second to finish. Now, we apply our optimizations, save and see that now the time is 100ms! That’s 900ms saved! Now, just in case we want to check the function again, before the changes. We remove our optimizations, save and… Whoa. 180ms. But the same code, just before took 1s to finish. Ahh, the programmer’s confusion…

But let’s break down what may have happened:

- Running code for the first time, we also started NodeJS server for the first time, it’s called a “cold start” (V8 really is like an engine). So the engine “saw” our code for the first time, and didn’t have a chance to optimize it fully.

- Next, we made changes to the code and ran the test again, this time, NodeJS is running and had a chance to do its magic and fully utilize its optimization tools, thus such a stark difference.

- Finally, we reverted code to its original state, but as with the previous statement, NodeJS doesn’t need to start from scratch, so it can optimize even our messy code.

You might be tempted to run the check multiple times to get the average execution time, but running the same code in V8 multiple times will cause it to remember the result, and present it to you without even running the code.

Part 2: Don’t trust OS

Let’s say we were able to turn off all V8 optimizations. Would our code run absolutely the same every time? Right? Right?…

No. Your computer does a lot of things in the background. You probably know that it occasionally checks for new mail, your location, software updates, and so on. It also has a lot of low-level processes like keyboard and mouse/trackpad interrupts, health checks, virus scans, and many more. It is unlikely that your application will run in such an isolated environment that at least some of these things won’t affect its performance. In the intro, I said that I unplugged my laptop from the charger. I intentionally mentioned this. See, switching from wired power to battery, forced the OS to reallocate power resources, and likely, NodeJS performance suffered.

In conclusion, you may tinker with V8 settings to opt-out of all optimizations for the sake of stability in your test, but your OS also has an effect on the performance of your code, and it’s unlikely you can control that.

Part 3: Don’t even trust your CPU

As I progressively descend into things I know less and less about, I still would like to take a shot at the last frontier of optimization: the CPU.

Modern CPUs have come such a long way and are such engineering marvels that it would take years of hands-on experience for an average person to fully understand their intricacies.

We don’t have that much time, but let me try to explain how the CPU may further optimize your code without you even knowing it:

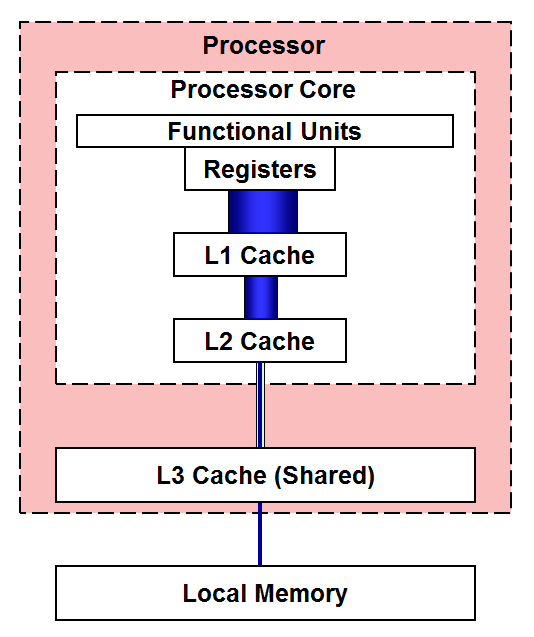

Instruction Caching: Let’s say we have a complex calculation running in a loop. You cannot cache the result as it’s always different, but the CPU doesn’t have to. Instead, it would cache the instruction set for the calculation in its L1 cache (see the image) instead of fetching it from memory every time. L1, L2, and L3 are small memory banks that are located in the CPU itself to help it fetch things it accesses often.

Branch Prediction: Imagine you’re driving and you come to a fork in the road. You have to make a decision about which way to go. Now, let’s say you’re very good at predicting which route is usually faster based on your past experiences.

That’s a bit like what branch prediction does in a CPU. When the CPU encounters a conditional statement in your code (like an if-else statement), it has to decide which path to take. If the CPU can predict which path the code will usually take, it can start executing instructions for that path before it knows for sure if the condition is true or false.

Conclusion

Our programs are slowed down and sped up by many processies some are always happening, some occur often and some randomly unless you want to detect sleep(5000) in your code that should run 2ms, blindly trusting the execution time of a function as a reliable benchmark can be misleading.